THE ANTEATER’S ANALYST

By Peter Tait with illustrations by Sarah Tait

The allegorical tales of Jeremiah Freak, as told to his grandson, Plumb Lucky, and passed down by their richly coloured housemate, the wealthy Macaw.

Contents:

1. The Anteater’s Analyst

2. The Centipedes’ Chiropodist

3. The Walrus’s Washboard

4. The Penguin’s Peccadillo

5. The Dolphin’s Depression

6. The Caw-Caw’s Cacophony

Part One: The Anteater’s Analyst

It is downtown Amazin’ in Central America – a manky, swanky little town where swarms of birds and beasts walk paw in paw through the local park and rock their young in the shade of the yo-yo tree. All is brightness and heat, full of garish colours and sweet scents. Around and about, the jungle hums and heaves like Piccadilly Circus and the cicadas sing little ditties their mothers taught them in their nests. The town is a little crazy, and everything throbs like a well-set migraine. An ungainly reggae beat reverberates along the vines, for this is reggae country, and the rhythm, once it begins, infiltrates the veins of the evening and draws everyone out onto the streets. And there, it’s party time, for as history tells us, there has always been a party in Amazin. And this goes on until after midnight, when the tropical downpours start, and it rains pumas and piddledash, as they say in this part of the world, and time slows to a mere canter.

The following day, the big orange comes out, the mud on the walkways turns a crazy pottery patchwork, the puddles drift slowly skywards. This is the life cycle of Amazin. It is a good place to bring up children. Crime is low, the piranhas have no teeth, shopping is easy. Fat cats and hood-eyed snakes parade their wares; no-one bothers no-one else unless they want to be bothered. No-one cares what the time is. Life, as they say, just sits there.

And there, in Amazin, in the middle of the jungle in the middle of Central America and just three jiggles down from the town park, is the office of Ambruzzo Emmet, District Analyst.

Dr Emmet was a particularly clever analyst and he had solved many problems in his long and wonderful career. Some of these were easy – why the polar bear felt homesick in Arizona took him less time to resolve than it takes to strip a banana, yet to understand why a hummingbird hummed in a single key was complex indeed. But as always, he found the answer in the end, amongst the sharps and flats of his busy life.

Dr Emmet was well-known and well-respected amongst his fellow analysts and was pleased he was, as he wanted to be thus. And he knew also that to be well-known because you are good at something is a fine thing indeed. Dr Emmet had good reason to be content with the problems life presented him with, partly because, at the end of the day, they paid for his lifestyle and his apartment in a jacaranda tree in Rio and partly because, however tricky they were, at the end of the day, they were always someone else’s problems. Yet that very day, his youngest daughter, Infanta, had anteloped with a termite, got married in Machu Picchu where the couple announced they were going to live in, of all places, a mud-tunnel inside a queñual tree. The temerity! And she could have been a queen one day!

It was on such a wet / dry and then wet again afternoon, that our visitor from out of town first knocked on Dr Emmet’s door, a door carved from the wood of a sleeping giant Dimple tree with a knocker shaped like a monkey’s mitt.

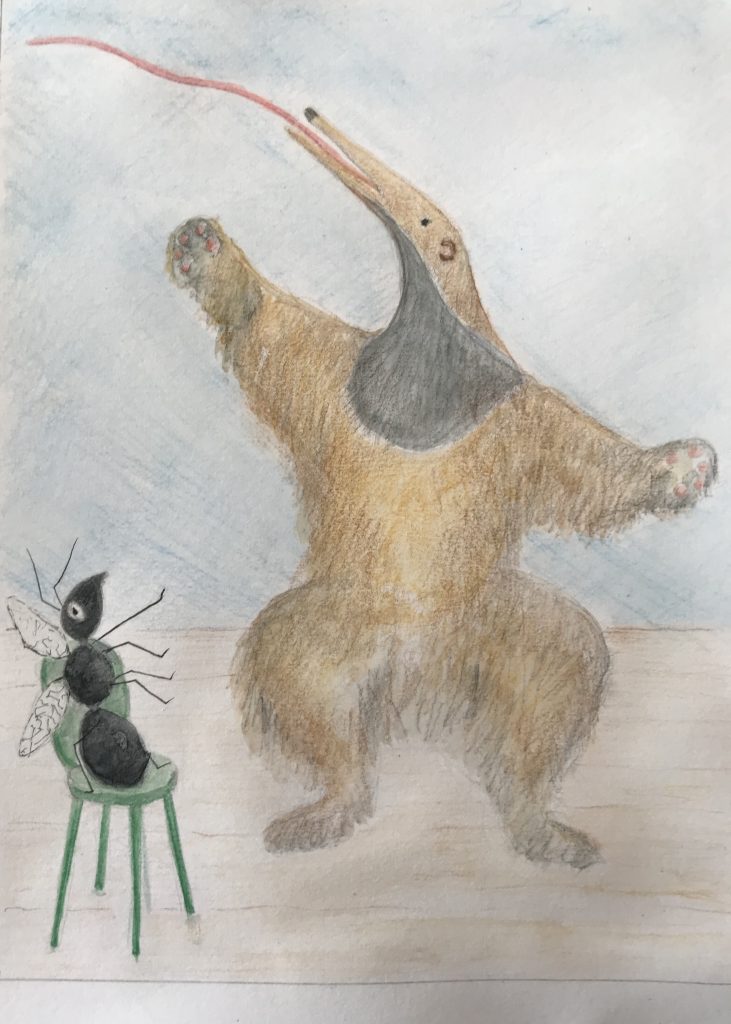

The doctor’s good secretary, Miss Placebo, who came from the coast when she was a wee lass on a wagon made of teak – probably ant teak back then – dragged by ten bullocks and who never knew her real father, opened the door as she was wont to do. She had worked for Doctor Emmet for umpteen years and was wise also although only Dr Emmet knew just how wise. There, on the step, she recognised her visitor as one of the great branch of anteaters, for she had met one or two in the past as they strolled through the savannah on their way from here to there, crawling on the sides of their feet.

“I’m Roberto Snoutsnacker, one of the giant anteaters, from the other side of the tracks” he snuffled in a damp, swampy voice that took forever to travel the length of his snout. “I’ve an appointment to see Dr Emmet.” He trembled with the weight of each consonant, but he was there and that was a thing in itself . And Dr Emmet was his last hope for he had hoped before.

She ushered him in, noting his save the earth tee-shirt and, rather oddly, all things considered, his vegetarian shoulder bag in which he carried his lunch and his smorgasbord of problems and anxieties. With his prehensile tail dragging the floor, his grey coat looking sadly undistinguished, one could clearly see he was a solitary being, a carpetbagger to boot and nervous with it, as his antics showed.

When she had filled in his medical records and paid his six antennas Miss Placebo ushered Roberto into the waiting room, all seven feet from snout to tail-tip, where he lowered his not inconsiderable (103 pound plus), bulk into a specious beanbag. From the evidence of his baggy skin he had clearly been much weightier once, before some form of malnutrition or food deprivation had set in. He did not have to wait long and before he had finished the article on how to iron out frizzy hair, Dr Emmet, bespectacled, grey and scruffy, as intelligent analysts tend to be, entered. Shuffling awkwardly forward, he ushered Roberto – Robert – Bob – through the anteroom into the foliage of his study. There, having made himself comfortable, Roberto – who we will call from hereon by the diminutive, Bob – started to tell his tale.

Bob cleared his throat and after a drink of water gathered from the leaf of the tequila tree, he started to unravel his life.

“I know I was always a difficult anteater, even when I was young, even when I was just a babe in swaddling leaves. I knew early on that the way I saw the universe was not the way others saw it. Like all infant anteaters, I was shown ant mountains and told to eat, but throughout my adolescence, I spent my time turning mountains into molehills and what anteater eats moles? By the time I was ten, I was an ostracised, over-sized anteater without a friend. My name was a misnamer. I was no longer an anteater, but I could hardly be called paw-paw eater either although that’s what I dined on. And worst still, some of my best friends were ants although it would have killed my mother to know that.”

Dr Emmet frowned. This was one befuddled anteater. He would need much counselling, which for you who don’t know, is a mixture of listening to a good deal of such rubbish and then saying lots of kind and knowing phrases in reply. Dr Emmet was good at counselling. He felt desperately sorry for Bob, not only because he was so upset, but because he would not like to be known by what ate – bigmaceater would sound plain dumb, he thought to himself. But he was in the first instance a very good analyst so he decided to analyse some more. This he did by listening and then nodding wisely at the right time. This was another skill he learnt at McAnalysis College.

“I know that I should just eat em up like I was taught when I was knee high to a pug-nosed ferret’ said Bob, “But once, when I was little I gorged myself on ants and I was violently sick. The memory of their pitiful eyes looking at me as I scraped them off my two foot of prime sticky tongue haunts me still. I remember thinking, here I am eating a whole army of ants, not just an odd battalion or two. I felt bad. I mean, as a boa constrictor who has eaten a buffalo feels bad. And I swore then, to give up ants and other insects for I could not abide those pitiful, beseeching eyes looking at me as they slipped up my snout. So I went vegetarian and that’s when my troubles started. I was starving trying to live off fruit mush and termites. I tried going vegan, but it was useless. And now my family’s disowned me, and my friends don’t want to know me. I am a no-mate anteater.”

He shifted uneasily on his claws, his long snout dripping the drips of upset. “That’s my tale, doctor. I need a survival kit. Can you help me?”

Dr Emmet sighed the sigh of a very brainy man. He paused long enough for Bob to feel uncomfortable, to wish he was back on the savannah. And then, just as sleep was about to fall like an open parachute (for he had walked a long way that day), the doctor stirred.

“Let me tell you a story”, said Dr Emmet, “for life is a story of sorts, except much more unbelievable, always, than what you or I could ever make up. This is a story of destiny. When you were born, your journey ahead was already decided. You would grow and age and then, when the time was ripe and the jungle called you, you would return to the landfill, like a rotting leaf. That is your destiny. And the ants on the savannah and in the jungle would build mountains on and around you and you would give them life and fuel and so life would go on, ant to anteater and back to ant. All this was planned to be and has always been. It was the same for the dinosaur. His destiny was to become extinct so he had to cut out meals, dumb down, learn how to fall over. Over time, he managed to do just that and one day he woke up and found yesterday’s threatened species (him) had succumbed and that he was no longer meant to be there. Amen. Job done. Destiny fulfilled. Adieu, dear Brontosaurus, thanks for the memory.

But sometimes, there comes along an extraordinary beast. I think you are one such beast, if I may call you that. You have asked questions about yourself that question the very being and purpose of you being on this earth. Sure, I could find you a quick fix for the food problem, prescribe a diet of stick insects; we could hide the ants in a pasta mash, but you deserve a better answer than that. Because the truth is always there, no matter how you dress it. You must learn why you are here, just like the bumble bee and the great white shark. You must accept your purpose on earth. You must not fight your very nature. And if Mother Nature put you on earth to eat ants, as I suspect he did, then eating ants is what you are about. You shouldn’t ever feel bad about the life you were programmed for, to use computer parlance. Look at you, all baggy sags and miserable. I’m not going to say go on trying to be a vegetarian. Not just because it would be a rejection of your true self and a denial of the feelings of all living things, but because you don’t have any teeth! Mastication is just out of the question. You’re not some dentured homo sapien who can make these choices. You can only consume what you can get on that rapid fire tongue of yours: ants, termites, maybe the odd bit of pulp. And if you had ever heard the wailing of the seed and the crying of the fruit, you would know that all things that grow have a soul and a destiny and that somewhere down the food chain, a little hurt is inevitable to all of us.” He paused.

“Mr Snoutsnacker, I tell you, be true to your nature. Ants think no more of you for not eating them. They know life’s dangers. After all, they are raised on mug shots of an anteater’s tongue. Moreover, you are part of life’s rich food chain and need to pull your weight. Rather, it is the paw-paw tree that feels betrayed for it doesn’t expect your snout to devour its fruit. Your nature is to eat ants. So go and eat ants. ‘Ant out’, to quote a humanism. For this is your birthright, your destiny in life, the pathway to finding yourself”

The anteater listened quietly to the wisdom of Dr Emmet and he felt good about what he had heard. And perhaps, (for it would take some time to adjust), if he ate more termites, (for whom he had little empathy), perhaps that would make it easier to get used to the idea of being a carnivore. And he had become rather portly and to cut back to, say, 20k insects a day would make him feel less bloated and better in himself, less of the glutton. And if he only chooses lean ants, deeply scorched with some greens and a little tom-tom sauce . . . .

And so, after a quiet meal of termite soup and ant and tomato pizza in the Orinoco Café, (for he had jettisoned his cut lunch of bamboo shoots), Bob returned to the jungle with a feeling of inner peace and not inconsiderable relief. So he could eat ants again. And anything else his sticky tongue could manage. And by doing so he wasn’t being cruel or unkind. He was just being himself.

Dr Emmet sat in his chair for a long time after the anteater had gone. He wanted to write up the case history but couldn’t find the energy. Sometimes, being an analyst when you are also married to a Queen Ant can be hard work. Yet just as the anteater was true to his nature, so was he true to his profession. It was just the sight of that twenty-four inch tongue that disturbed him. And the chilling thought that after every problem in the world had been solved, who then would look after the analyst.

Glossary:

Adieu = bye bye (French / foreign / pretentious – Dr Emmet playing the bilingual card – customers should expect to pay extra)

Adolescence = position in life at centre of universe (see universe – below)

Analogy = (a) story that is the same but different (b) ant rash

Analyst: A person who studies things and who traces problems back to where they started. For instance, if you’ve got earache, it’s probably from your i-phone.

Antic: The cause of Dr Emmet’s twitch

Antelope: When ants run away together in order to marry.

Antenna: A tenner (£10 note) although rates fluctuate between colonies

Antique: Type of teak most favoured by ants as resistant to termites

Antwerp: A very silly ant

Bloated = If you mix three pounds of rice and three litres of water, you’ll get the idea.

Carnivore: Someone who eats meat until mad cow strikes (Appropriate Funereal song: ‘The Carnivore is Over)’

Complex: Just forget it.

Emmet: The word emmet comes from the Old English aemette, which means ant. It also refers to tourists who visit Cornwall because like ants they are often red in colour and appear to aimlessly mill about.

Empathy: To feel the same as someone else – when they hurt, you hurt; when they eat ice-cream, you smile unless you have a hole in your tooth then it’s not empathy

Humanism = a term used by humans, a poor pig’s animalism

K = 1000. Used by inhabitants of top tax bracket

Picadilly Circus: Place in London – Common to all circuses, full of clowns, wild animals, peccadillos and tattooed ladies.

Profession = posh job – no standing required

Rio = a nice place to party

Succumbed = Died. A terminal condition. Not to be confused with “succumb again another day” which implies a return – not possible here, I’m afraid.

Tongue: The anteater’s tongue is a joy to behold. According to that veritable old institution, the National Geographic the tongues of giant anteaters can grow up to two foot long and are coated in a sticky saliva which can flick in and out at a rate of 150 times per minutes. A sticky end awaits.

Trait = sign, mark, characteristic. Person whose main personality trait is to dump on friends is known as a traitor.

Universe = earth and stars all mixed together; if travelling see hitchhikers guide.

Vegetarians and Vegans: Just to pre-empt any trouble from interest groups, this story is not about you – some of my best friends are vegetarians and vegans. For we humans, it’s a good fit if you’re that way inclined; not so for anteaters.

Vores: All humans are vores. Carnivores eat meat, herbivores eat plants and vegetables; omnivores eat anything and everything. Vegans are a subset of vegetarians. If humans are hungry, they are often described as carnivoracious, herbivoracious etc

Educational Tip: For information about the anteater, go to https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/64660/15-majestic-facts-about-anteater or https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/mammals/facts-about-giant-anteaters or, for a youtube clip, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bo_nh49_-e8

Morals of the Tail:

- That we need to be true to ourselves and to our nature

- That we each have a purpose in life and we should seek to fulfil that purpose

- That when we trip up and lose our way, there are always wise people out there, ready to help us.

- The food fads are not just for children

- Moderation in all things is always best